Based on Maggie O’Farrell’s prize-winning novel of the same name, Hamnet centres on Agnes Shakespeare, a woman who has remained an enigma for centuries. In this adaptation, she is finally given centre stage, and the collaboration between Jessie Buckley and director Chloé Zhao in bringing her to life is quietly resplendent.

Hamnet is, very openly, a story about grief — like much of contemporary British cinema of late — but there is arguably a more powerful theme running beneath this period drama: female independence. Agnes does not meet the expectations placed upon women of her era. She delights in solitude, spending time among animals and nature, and is unperturbed by male attention. She has a life of her own, and she is content within it. This spirit of self-sufficiency persists even after she marries and has children; she often remains dirt stained and dishevelled and the idea of living apart from her husband does not deter her from her role as a mother, nor does it diminish her sense of self.

And though Agnes’s husband’s name hangs over the title, this is emphatically her story. Walk into Hamnet blind, and you may be genuinely surprised when it is finally revealed that Paul Mescal’s idealistic character is a young William Shakespeare. Zhao deliberately decentres him by withholding his name for much of the film, and Mescal — clearly understanding the assignment — shrinks his presence so that Agnes carries the emotional weight, even during moments traditionally framed as shared, such as childbirth.

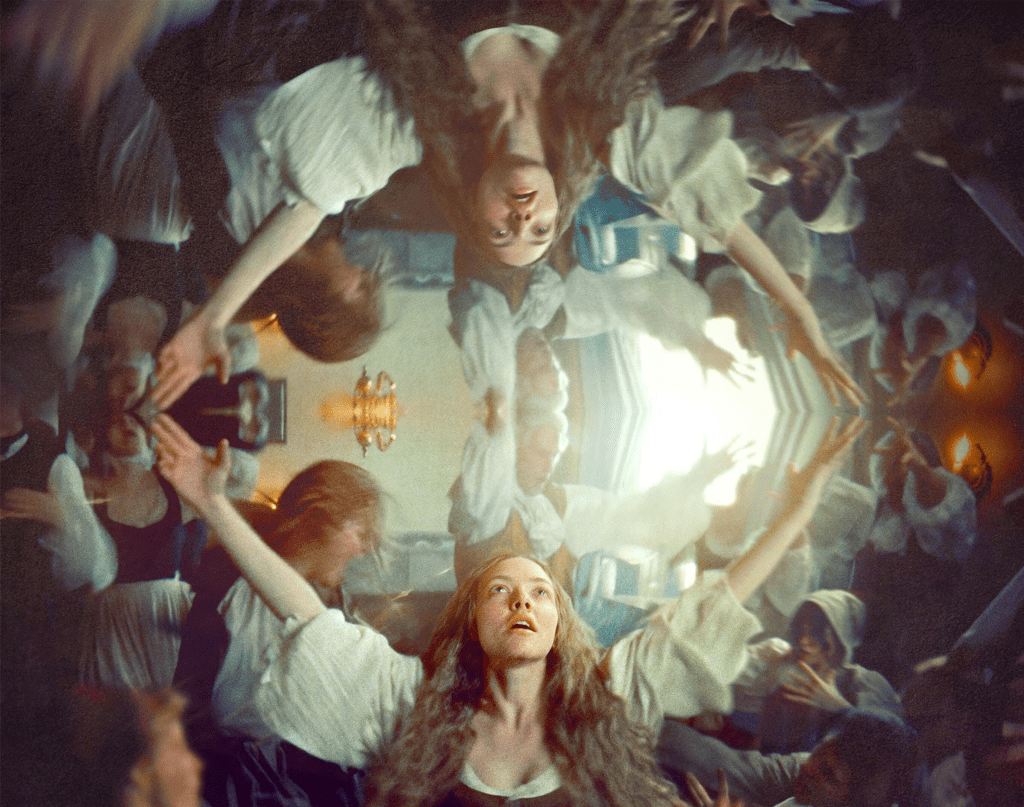

At times, Hamnet feels like a Jessie Buckley audition reel, showcasing her ability to be feral and free, commanding and vulnerable, often within the same breath. Thankfully, she is utterly captivating throughout. The film resists turning Agnes into a muse or moral anchor; instead, it presents a woman rooted in tradition yet carving out meaning, agency and survival in a world that offers little space for female autonomy.

Chloé Zhao’s authorial trademarks are present too: an attentiveness to landscape, an interest in quiet communion, and a refusal to over-explain emotional beats – that’s okay thought because the musicians raid every emotional instrument in their arsenal for the score — and it bloody works. Swelling strings coax feeling without overwhelming the film, supporting the visuals during its overt emotional moments while landing just as hard in the softer scenes.

Overall, Hamnet offers an intriguing, thoughtful and emotionally resonant portrait that asks us to reconsider the gender narratives we elevate — and which we allow to fade into the footnotes.

Check out what else I watched during BFI London Film Festival 2025

Leave a comment