This extraordinary film charts the life of a Hungarian born architect and holocaust survivor who starts a new life in the land of freedom and opportunity. Director, Brady Corbet, underlines the fine print of this American ideal that, for migrants, with freedom and opportunity comes tolerance and isolation.

Crafting a movie that is 3 hours and 30 mins is no small feat. It’s a lot of time to try and hold an audiences’ attention, and forms a trap for the writer to fall into self-indulgence. Gratefully, Corbet, who co-wrote The Brutalist with Mona Fastvold, can be forgiven for moments of frivolity because the movie may be bleak, but it is never dull.

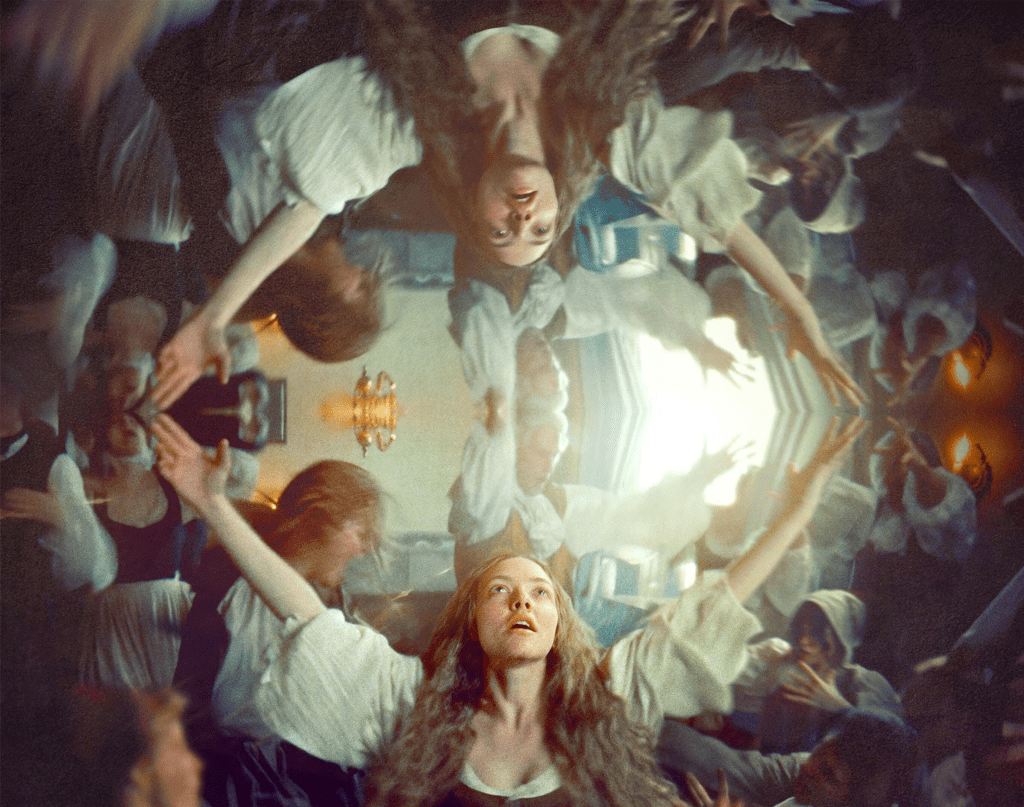

As soon as László Tóth (Adrien Brody) steps foot in America, his life becomes a dance. One step forward and two steps back. He has escaped the unimaginable, but he is alone, with his wife Erzsébet (Felicity Jones) and niece trapped in Europe. Journeying from New York to Pennsylvania, he is overjoyed to be reunited with his cousin Attila (Alessandro Nivola) and given a place to work and live until he gets on his feet.

It goes well until Attila chooses his assimilated life; a Catholic wife and American accent, over his cousin. The microaggressions are slight, with Attila’s wife commenting on getting László’s nose (broken in an accident) fixed, but it is clear László doesn’t fit with the American dream they have bought into.

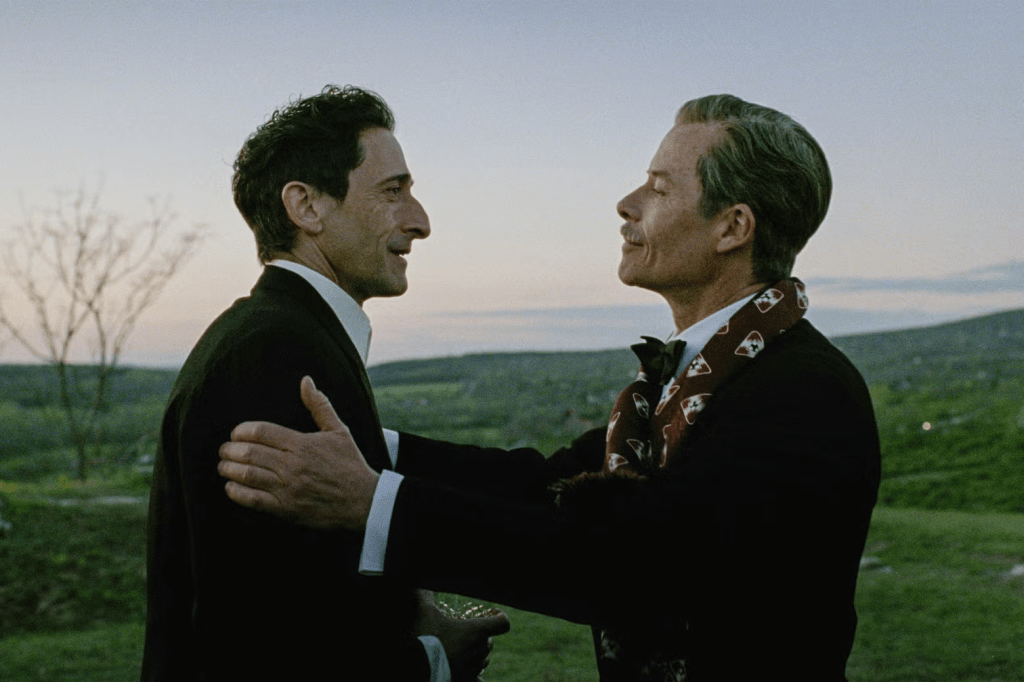

It’s not all gloom and doom – László’s life is changed when wealthy snob, Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce) commissions him to make a community centre with complete artistic licence. Harrison, on multiple occasions, remarks to László “I find our conversations intellectually stimulating” however László challenges Harrison’s perceptions of emigration and his open reverence of László’s creativity masks a bitter jealousy.

This message is reinforced over and over as László stands silently by while Harrison makes disparaging comments about poor, and at a party dinner remarks that László sounds like a shoe shiner. This scene is sublime in its cringe-worthy awkwardness. Harrison adds insult to injury by tossing László a coin (part of the shoe shiner ‘joke’). László is caught off guard and the coin clatters to the floor. As a final twist, Harrison asks László to retrieve the coin and hand it back. It’s beautifully directed in its clumsiness, and the framing of this scene says a thousand words.

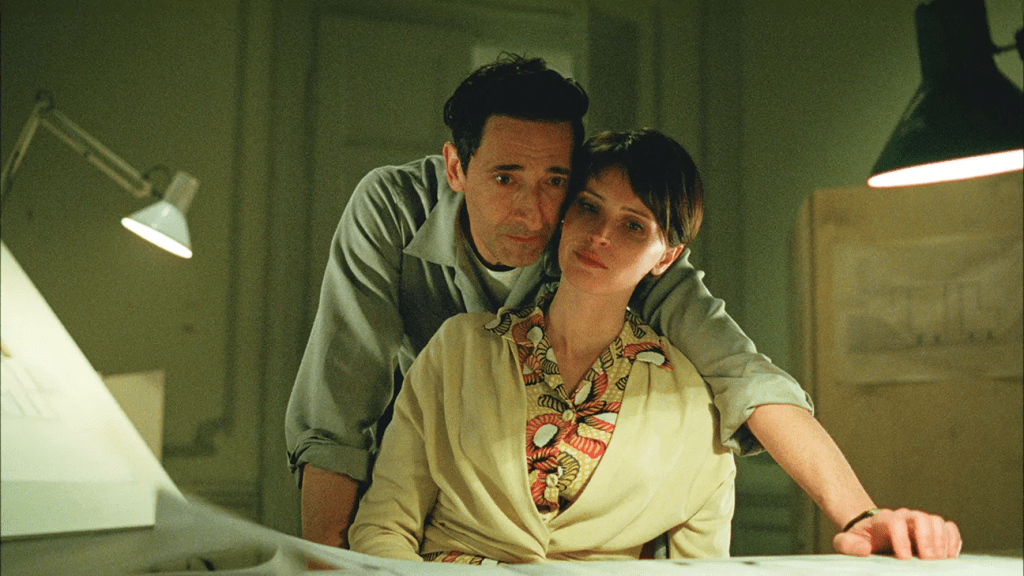

This dinner party is Erzsébet’s initial introduction to her husband’s patrons. The camera focuses on husband and wife, who avoid eye contact. Erzsébet’s is vocal but polite in admonishment of Harrison’s words, while László’s sits quietly. You feel his shame in having his wife witness how he is treated, and his silence confirms he will continue to endure this behaviour for the opportunity Harrison has given him. This scene brilliantly foreshadows Harrison, Erzsébet and László’s reactions to an event in the later part of the movie.

László is trapped. The only moments of freedom where László is accepted as himself is in the company of his friend Gordon (Isaach de Bankolé).

A Black single father, Gordon, like László, is an outsider to the white American’s. He may have been born in the US (this isn’t explicitly mentioned) but segregation is still decades from abolishment, and so Gordon is looked down on by most of the people around him. Except László.

We don’t see anyone else interact with Gordon, and so he starts to feel like László’ invisible friend. This speaks to the erasure of marginalised groups, who form kinships based on shared experiences of tolerance in spaces they have a right to belong. It’s lonely and isolating.

Erzsébet and László have dinner with Gordon and his son, and it’s a stark contrast to the dinner with the Van Buren’s. There is no showboating, only a vulnerability we haven’t yet seen from Gordon, resulting in a strengthened kinship.

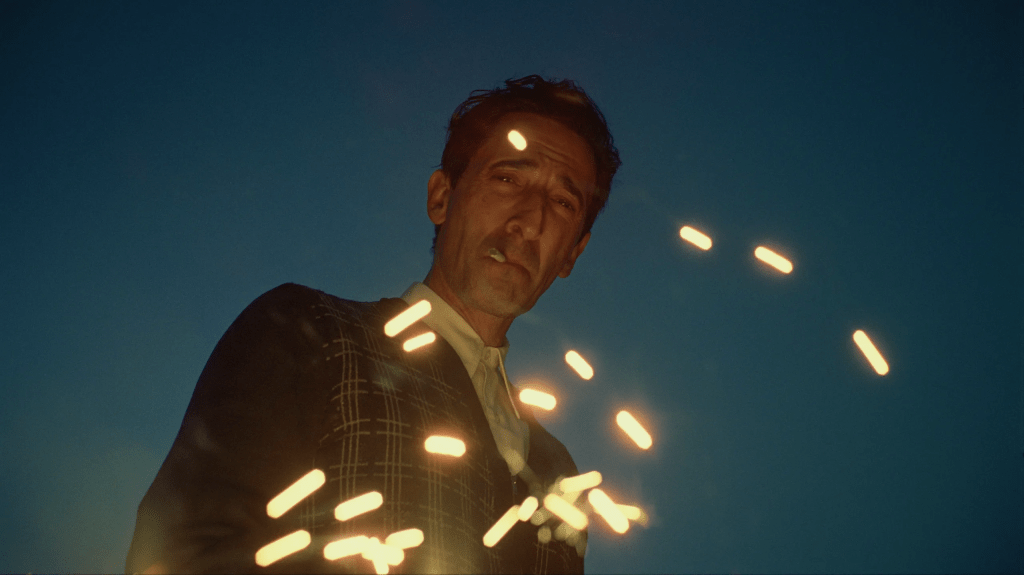

As The Brutalist unfolds, László becomes a living museum exhibition—his life displayed in curated moments that shock, delight, and disturb.

An exhibition is only as good as its subject, and Adrien Brody brings to life an astoundingly tender, complex and passionate László Tóth. There is a scene a little over halfway when the camera approaches László, who is working at an architectural firm. We recognise his gangly and consuming pose as he stretches out over his drafting table. Then he turns at the sound of his name and smiles.

It’s the smile of an old friend, and your arrival has made their week. It’s full of hope, and it is utterly heartbreaking because it confirms his continued endurance. László, who had vowed to never work for anyone but himself, has had no choice. But now, he will return to being treated like the help despite the esteem of his profession, in order to see his vision come to fruition.

Narratively, the second half of The Brutalist builds on the foundations of the first with László eagerly anticipated reunion with his wife Erzsébet and niece, Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy). The introduction of these two characters see’s a shift in focus from László’s ongoing endurance that is not as strong as its start.

The trouble with the introduction of Erzsébet and Zsófia, is that the script never fully commits to exploring their own stories and struggles of immigration. Erzsébet and Zsófia travel from the Van Buren’s to visit Attila, but we never see their reunion. Frustratingly, despite the weighted set-up from part one where we now anticipate a confrontation with Attila over his treatment of László… The moment never arrives.

In another example, there is a charged and lingering moment between selectively mute Zsófia and Harry (Joe Alwyn), Harrison’s pretentious son. We make our own assumptions about whether anything happened between them, but it is never referenced again.

Unfinished moments like these make it hard to find closure and affects the film’s emotional weight—diluting the impact it could have on the audience. With a running time of over three hours, surely there would have been space for the women. To glimpse Erzsébet’s own struggles at work, or find joy in Zsófia speaking for the first time since the camps, and relate this back to László’s story.

The second key difference with the second half of The Brutalist was the abrupt change of tone as it shifts towards something sinister, which contrasts with the film’s earlier subtlety. Character wise, Harrison – transforms from mildly detestable to a full-fledged monster and the climax of the movie, which involves a confrontation, was overdramatic to the point of disbelief. One moment you are watching a movie and the next the shock effect of sudden theatrics transformed The Brutalist into a play, causing a tonal disconnect between parts one and two.

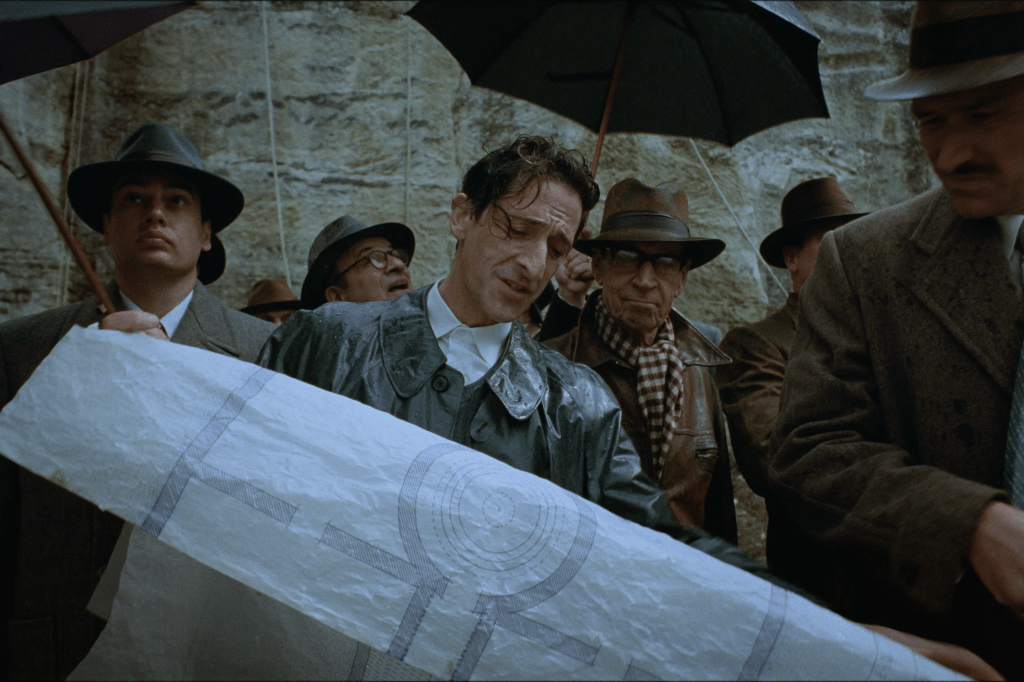

The Brutalist is undeniably a cinematic feat. Shot using VistaVision – which involves shooting horizontally on 35mm film stock – the process also gives an aesthetic feel that added an easy authenticity to capturing the era.

Much like the Bauhaus style we see throughout the movie, The Brutalist tells a story that is severe but enduring. If you are a fan of sweeping narrative that entwines you in the life of a single character, then time will fly as you meander through the life of László Tóth, who, like his work, leaves a lasting impression.

Brody a career defining job bringing László Tóth to life, in a way that makes you believe the Hungarian born, architect is a real person. He was not. This pseudo fictionalised biopic however is said to be inspired by the lives of Ernő Goldfinger and Marcel Breuer architects and furniture designers of Hungarian descent.

Like László, Goldfinger and Bruer emigrated from the countries they were born. The Brutalist shows the raw reality of the quiet struggle migrants face even today, finding greener pastures but living with darker clouds.

After exploring the ugly truth of an ongoing battle for acceptance, The Brutalist begs the question; is it even worth it?

What did you think of The Brutalist? An epic masterpiece or an utter snoozefest?

Leave a comment