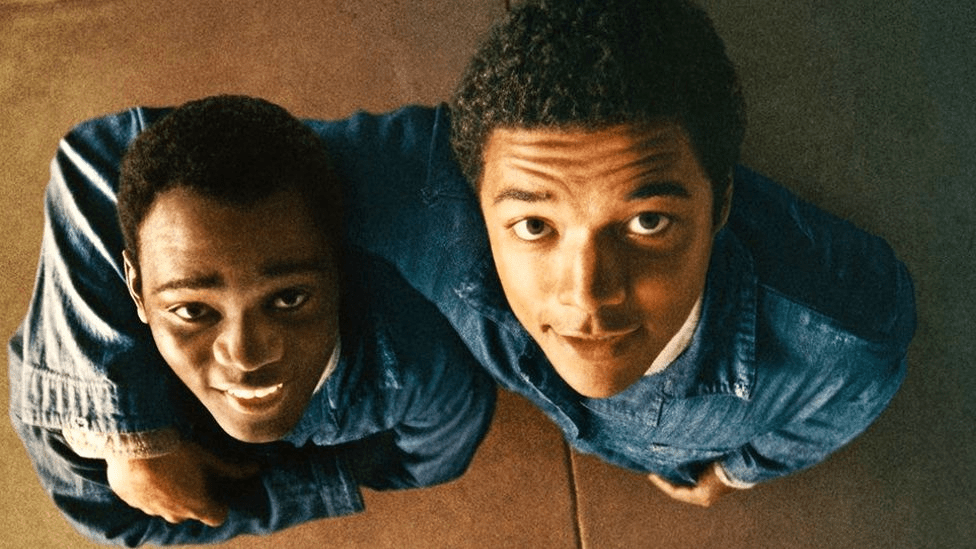

Based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead, RaMell Ross directs Ethan Herisse and Brandon Wilson in this heartbreaking tale of survival, friendship, and the unyielding weight of injustice.

In Jim Crow era America, a chance encounter puts Elwood (Herisse) on the wrong side of the law, and he is taken to Nickel Academy, a segregated reform school in Florida. Here, the promise of freedom is dangled by the corrupt staff, who preach a tiered system for good behaviour while they abuse the children in their care. It is here that Elwood meets Turner (Wilson), and the two young men form a lifelong bond.

When we meet Elwood, he has a future.

We watch Elwood grow from a boy playing beneath sheets, running free in the garden, to a young man, getting good grades, a girlfriend, and becoming involved in the fight for equality in the South. Elwood is loved dearly by his grandmother played by Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor who makes a lasting impression in her supporting role. Elwood is good, he is smart, and his behaviour is rewarded when his teacher puts his name forward for a full ride to college.

Then, in an instant, when Elwood gets into the wrong car, we watch the flicker of hope for his bright future get snuffed out. From this moment, Elwood’s life is split into two: the life he leads, and the one he should have led.

“What if” becomes a constant gnawing theme. Useless phrases that run through our mind, like “If only” and “Why did he…?” only aid in emphasising the disproportionate policing of Black boys in America – an issue that echoes through to today. The idea of an alternative life for Elwood hangs over the rest of the film, acting as both a curse and a cure for our inability to rewrite Elwood’s tragic fate.

The fictional Nickel Academy is based on a real school, the Dozier School for Boys in Florida. The reform school, which was an alternative institution for prison for young offenders, acted as a law among themselves, often committing atrocities against the young boys in their care. Although the film is never explicit in the abuse faced at Nickel Academy, it instead plays on theatre of the mind.

There is a scene where Elwood, after standing up for a group of young boys at the academy, is dragged from the dormitories in the dead of night. One by one, all parties involved—blameless or otherwise—enter a room with the school administrator (Hamish Linklater). We never see what happens to the boys in that room. The oppressive sound of a machine scatters our senses, the palpable fear among the boys who whimper and shake before they enter the room. The administrator folding up the sleeves of a bloodied shirt, and asking Elwood to ‘climb on’. Through these fragments, we are left to piece together the horrors faced as the camera cuts to black.

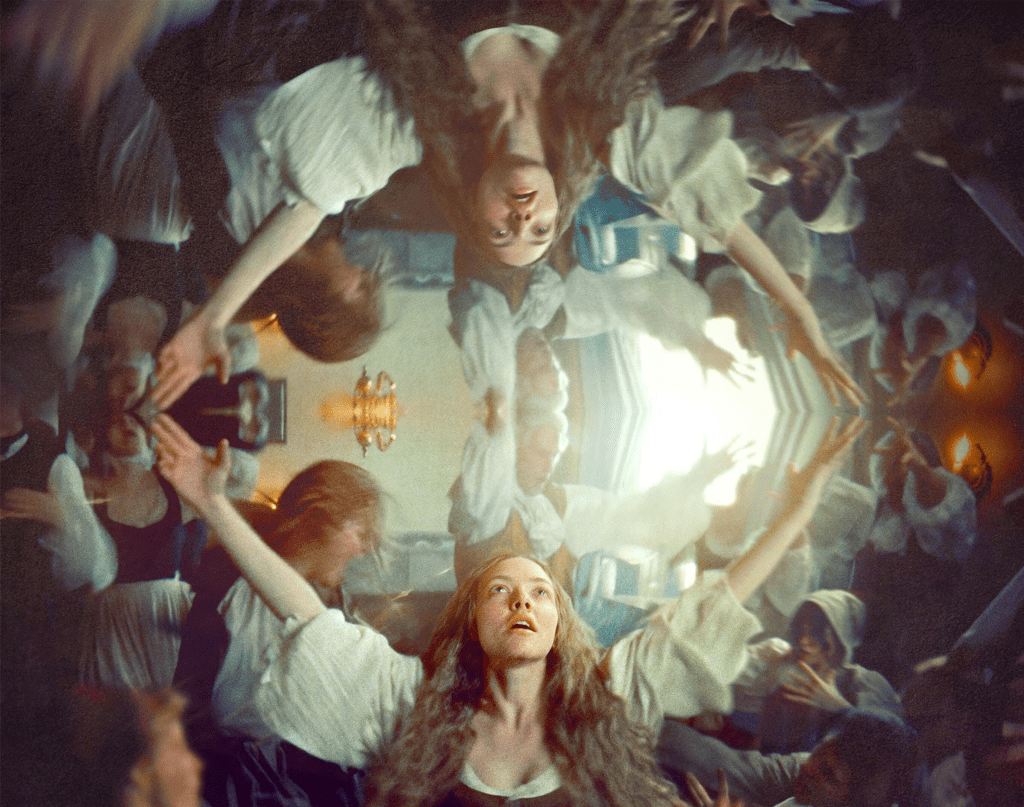

It’s a clever technique Ross employs, the cutting to black akin to Elwood blacking out the traumatic experience. It’s a thankful saviour for the audience, who for the movie are forced into the driver’s seat for Nickel Boys, thanks to the ambitiously effective first-person POV cinematography style. The VR effect feels unnatural at first and a little wobbly around the edges, but this claustrophobic intimacy makes the narrative personal. It is impossible to distance ourselves from Elwood’s experience.

We don’t just watch his story, we live it.

Because of this, we don’t get to meet the quietly resilient and secretly hopeful Elwood face-to-face until we reach an unexpected change of perspective and switch into the form of lone wolf Turner. This change of view gives us our first direct look at Elwood, and entwines the lives of the two boys. Turner in comparison to Elwood is familiar with the stench of hopelessness, which is highlighted by his harrowing perspective that “life isn’t much better on the outside.”

Turner stresses to Elwood the importance of looking out for yourself, and forces Elwood’s hand in conforming to this point of view by hiding a letter from Elwood’s grandmother in order to crush his spirit.

Herisse who starred in Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us channels a similar gentleness to his role as Elwood. Paired with Wilson, the two are harmonious in their grounded depictions of strangers-turned-brothers, forged from the shared trauma of the Academy and life as a Black boy in America.

One of the ways the movie transports the events of Nickel Boys beyond a historical drama is by allowing us restricted glimpses of Elwood’s future. Viewing life as adult Elwood (Daveed Diggs), we are booted out of our familiar front-row seat and instead hover spectrally behind him as he goes to work, goes to the bar, and interacts with his partners.

This has a deeply moving effect, serving as a visual representation of being haunted by a past you can’t shake. This rhetoric of hauntings continues as we see adult Elwood, over the years, keep tabs on news of Nickel Academy as its dark deeds slowly resurface.

Seeing adult Elwood is an indicator that Nickel Boys isn’t only a movie about injustice, it’s also about resilience. By combining fiction with fact, it takes us beyond a conventional historical drama and into the realm of lived experience. It doesn’t just recount events; it immerses us in them. The movie isn’t always explicit in what the boys faced, but it doesn’t need to be. We know. We’ve read about it, watched movies, heard the stories. However, Nickel Boys forces us to confront this history as something deeply personal and visceral.

By the end, we’re left with an overwhelming sense of loss, not just for the characters but for the countless others who endured similar fates. The melancholy lingers, a powerful reminder that the past stays with us and its scars remain.

What did you think of Nickel Boys?

Watched during BFI London Film Festival 2024

Leave a comment