Fingscheidt, Liptrot and Ronan are a holy powerhouse in this effortlessly relatable film of growth and finding strength in isolation.

Rona (Saoirse Ronan) has returned home to the Orkney Islands. Not by choice, by necessity. After an incident led to her spending time in rehab for alcohol addiction, she left London, hoping time apart from the chocking grasp of the city would allow her to find her feet.

Living with her Christian mother (Saskia Reeves) and spending time with her father (Stephen Dillane), who struggles with depression, Rona’s past present and future crash together as she wades to find a path out of darkness and into the light.

What is both unsettling and true about Rona, a friendly, smart, bold woman, is that she could be anyone. That best friend you make in the toilets on a drunken night out and never see again, the colleague that drank a little too much at the Christmas party, that person lying black out drunk you walk around on your morning run. Rona’s downward spiral is imperceptibly, directed by Nora Fingscheidt, with Ronan at the helm of this turbulent ship. There is no trigger, it is this thing that seems to have lain dormant until it was ready to wreak havoc and be named: Alcoholism.

Based on the memoir of the same name by co-writer Amy Liptrot, The Outrun manages to feel both familiar in the inevitable fallout of addiction and all it impacts, and yet wholly unique. This is one woman’s story, one woman’s journey, and yet it brings the audience into the fold, tying us to their journey with a thread of relatability. The most heartbreaking line in the movie is utterly banal. It is forgettably familiar. We’ve said these words, had them said to us, and coming from any other person on any other day being asked; “Do you want to go for a drink?” wouldn’t be so devastating.

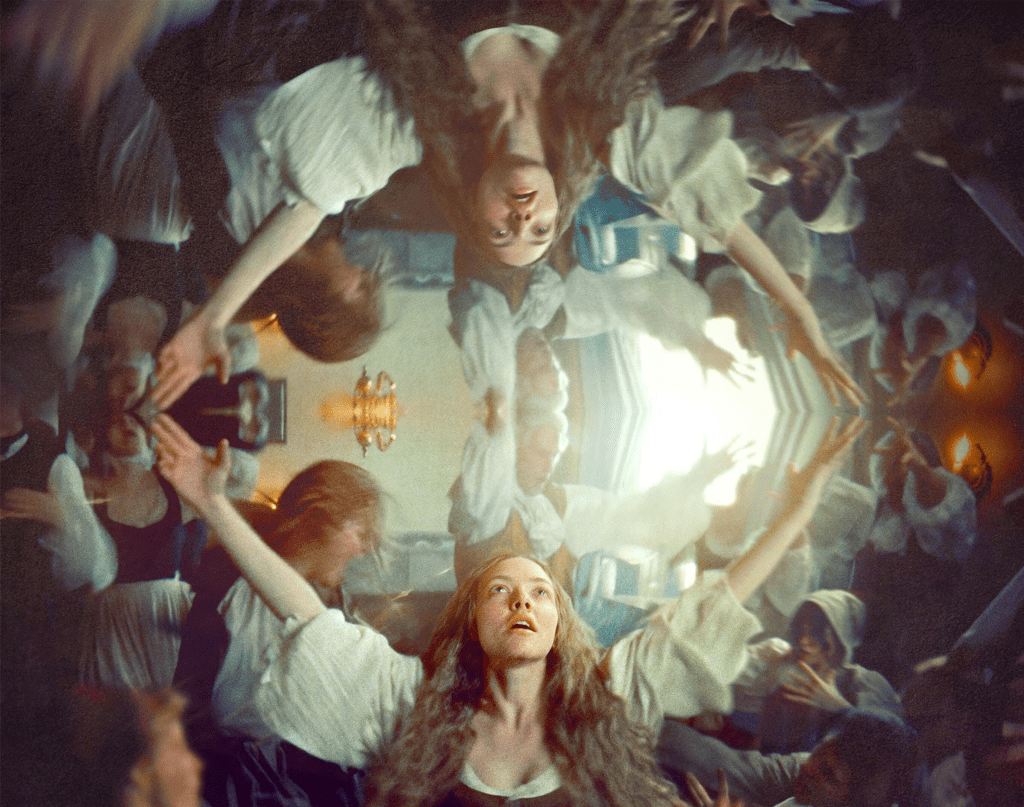

The narrative plays out over three core timelines, and Rona narrates us through the phases of her life as if she’s reading entries from a scrap book journal filled with doodled animation, fantasy and poetry. In the present, Rona fights to stay sober and sane, a quietly simmering energy compared to the Rona we see in the past. Confident then calamitous, as we understand what drove her to finally seek help.

Finally, we have snippets of Rona’s childhood, where she watches her mother try and fail to save and stay with her father, who battles his own demons. The parallels are obvious and although it isn’t explicit, in true millennial form it begs the questions does not all present trauma relate back to one’s parents?

These events effectively weave in and out of one another. Sliding doors of past present and future that add weight to the timelessness of Rona’s struggles, because in Rona’s case, addiction isn’t something that starts and stops. There is no definitive beginning, a moment of realisation, or a way to shut that chapter in her life. The same way it her addiction can’t be linked to a specific time, it can’t be linked to a place.

However, Rona is only human and there’s nothing like London to push you down at your weakest.

London is a trigger. The drinking culture is rife, as it is throughout the UK to be honest, however London is the source of Rona’s memories; the bad, the worse and the ugly. Whatever good times there were, like her relationship with Daynin (Paapa Essiedu) has been eaten away by the darkness leaving nothing for Rona to hold onto. The prospect of returning to London is claustrophobic and so Rona chooses to stay in Orkney, and when that doesn’t provide the solution she hoped, she pushes herself further away, isolating herself on one of Orkney’s smaller islands.

There is something incredibly powerful about choosing to be alone when society is always pushing people to socialise, to share problems and to couple up and copulate. Isolating yourself is typically viewed negatively, but sometimes, as Rona shows by opting to stay in that freezing cold cabin throughout the winter, you need to do the hard things on your own. On that wonderfully desolate and unapologetically uninspiring island, Rona begins to heal.

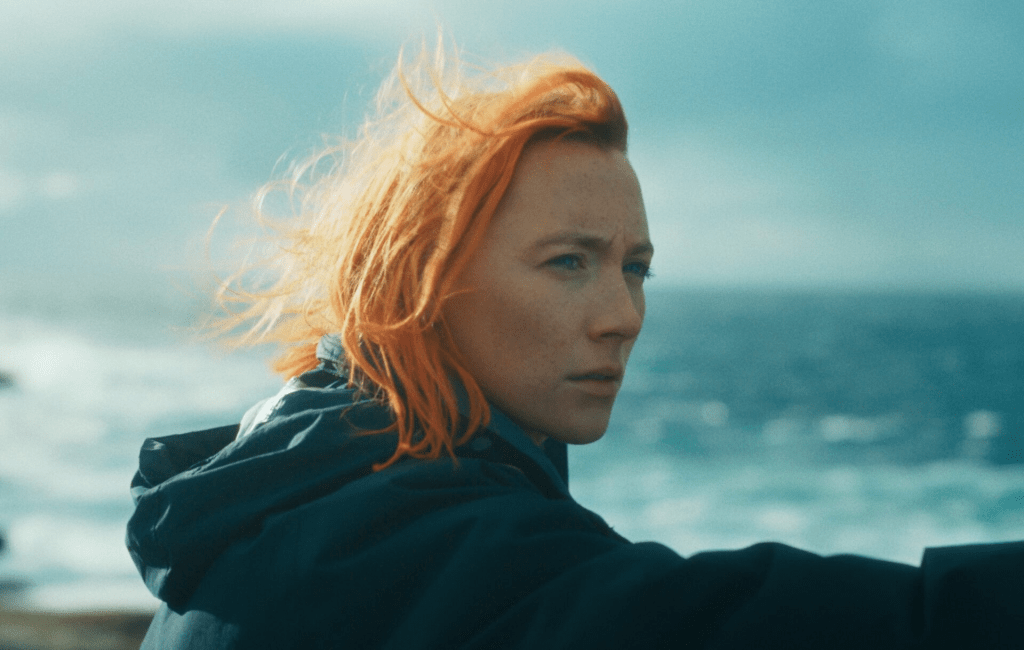

There is a joyous moment where Rona dances around her little cabin, house music blaring, moving from room to room with the non-stop energetic, sweat soaked abandon you typically save for the club. Ronan is resplendent, as she knits together in one scene the Rona we meet in London and the Rona we know from Orkney. Dying her hair a bright, fearless orange, Rona finds a way back to herself.

The cabin satisfies that feeling deep desire within to run away, to escape to destinations known or unknown that we believe will fix everything, but, The Outrun reminds us that wherever you go, there you are. It’s okay to step back from everything, but eventually, when you’re ready, you’ll find that facing your problem head on, allowing yourself the room to make mistakes, forgive yourself and grow, is where life is.

Leave a comment