Sing Sing, a maximum security prison, houses a company of prisoners turned amateur actors taking part in the Rehabilitation Through the Arts programme. Amidst personal issues and contemplative observations, the group prepare for their next performance.

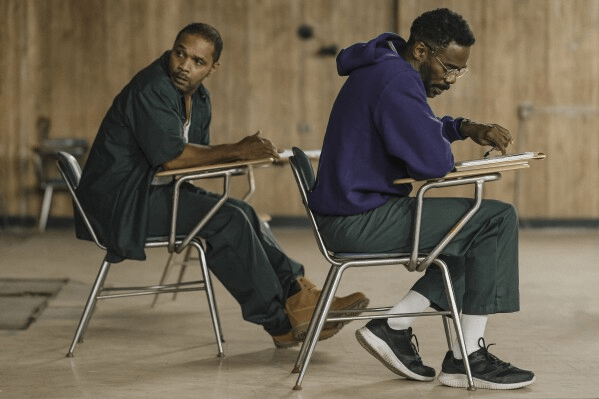

The screenplay was written by Clint Bentley and Greg Kedwar with Kedwar directing the feature. Based on The Sing Sing Follies by John H Richardson, alongside professional actors Colman Domingo and Paul Raci are formerly incarcerated men, who have lived experience of the films central component: Rehabilitation through the arts.

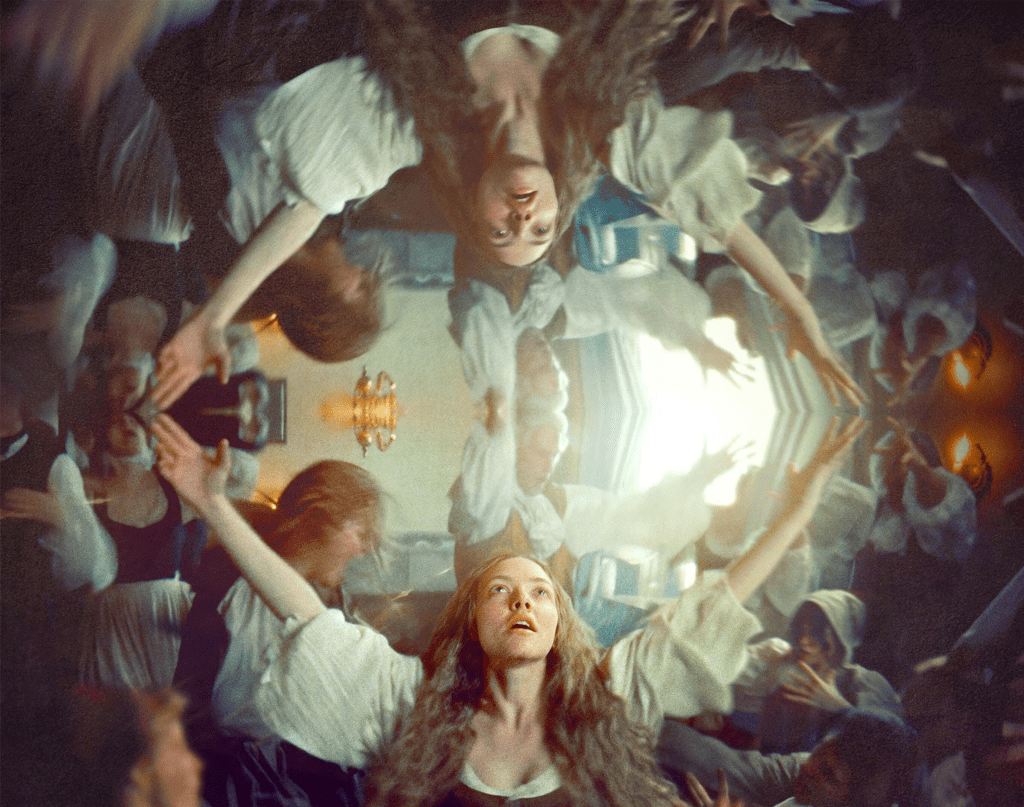

The opening to Sing Sing sets the tone for the movie, as we watch John “Divine G” Whitfield (Coleman Domingo) perform the closing soliloquy to A Midsummer Night’s Dream. His steadfast tone and the belief in the character he embodies transports not only himself, but the audience, who meet the end of his speech, with thunderous applause. The lights, the stage, the costume, that brief transportation into the heart and mind of another person that only theatre can give you is gone in the blink of an eye, and we meet the real Divine G. An inmate at a maximum security prison.

Standing obediently in line, wearing a green two piece, he is so far away from the man we met only minutes before. Gone is his elevated title of performer: this is his everyday. Part of the crowd, one of a sea of faceless many.

It wasn’t an accident that we first meet Divine G the actor, followed by Divine G, the inmate. The film underlines from the start that this isn’t your stereotypical ‘prison drama’. Sing Sing brings to the forefront a theme which many movies in the genre forego for shock, fear and violence. Humanity.

Sing Sing cleverly plays with our expectations of prison drama’s through the character Clarence “Divine Eye” Maclin (played by himself) who, in the eyes of Divine G, and ourselves, has joined the Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA) programme to sow discourse. Initially we label him antagonist, and enter an unspoken agreement that Divine Eye deserves to be in Sing Sing and Divine G who presents as educated, reproachful and innocent, does not.

We make these assumptions before we learn how these characters ended up at the facility. Through throw away admissions of reality and heart aching scenes of resignation, the movie leans into our assumptions and takes us on a journey to understand the importance of the RTA programme in both these men’s lives.

The meta nature of Sing Sing works when it works and distracts when it doesn’t. A key component of the film, which gives the story an authentic weight is that most of the inmates on screen are playing themselves. Formerly incarcerated, now rehabilitated. In the film you feel the depths of their experience during moments of bonding when they sit in a circle between acting exercises. They share stories and briefly exist only as a troupe of actors, ignoring the reality of their situation. These moments work by giving the film breathing room, however, ironically feel so true that it pulls away from the relative fictional world that has been created.

The quiet, brewing nature of Sing Sing is what makes the movie… sing. The isolation of the RTA group despite prison life ticking away in their periphery, and the counter-balance of Divine G and Divine Eye’s characters. Sing Sing serves as a reminder that life in prison, is still life, and acting in its basic, most natural form is freedom.

Leave a comment